|

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 02 février 2009, 01:48 |

Membre depuis : 15 ans Messages: 5 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 08 février 2009, 04:24 |

Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 1 622 |

léne

salut

desoler je n'ai pas de photos de la librairie de Mogador

c'etait la seule celle de Monsieur BENDAVID

de la rue Allal Ben Abdallah (devenue ce jour magazin de photos)

donne moi une indication des personnes que tu cherches

ds les rues a coté

il y avait

famille Sebag ( fille Orly)

Famille BENOILID (imprimeur de metier)

en face il yavait une famille Cohen et AMZALLAG

apres c'est d'autres mais un peu plus loin

comme ABECASSIS et BENSABAT (une rue de droite et une de gauche)

David Bouhadana

salut

desoler je n'ai pas de photos de la librairie de Mogador

c'etait la seule celle de Monsieur BENDAVID

de la rue Allal Ben Abdallah (devenue ce jour magazin de photos)

donne moi une indication des personnes que tu cherches

ds les rues a coté

il y avait

famille Sebag ( fille Orly)

Famille BENOILID (imprimeur de metier)

en face il yavait une famille Cohen et AMZALLAG

apres c'est d'autres mais un peu plus loin

comme ABECASSIS et BENSABAT (une rue de droite et une de gauche)

David Bouhadana

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:06 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

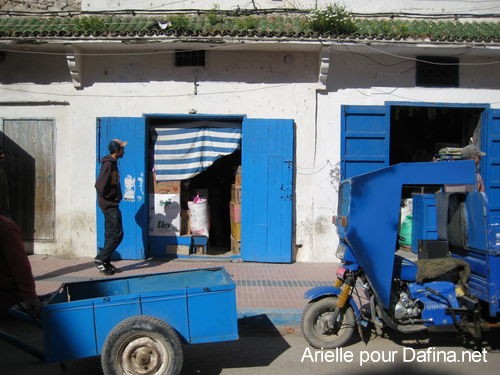

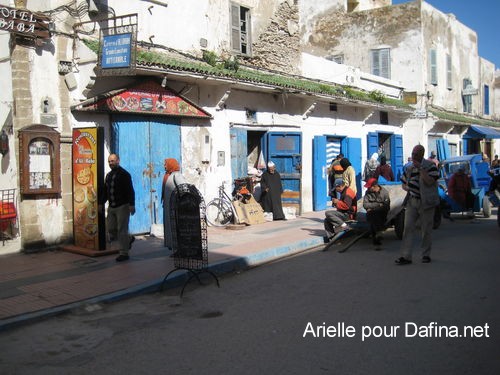

Pour Echkol qui nous a tant gate avec des photos de Mogador, et pour tous les amoureux de cette ville.

Quelques photos rescentes qui m'ont ete offerte par un ami qui a voyage a Essaouira cet hiver.

Je sais on les a vu 1000 fois, mais bon c'est un nouveau regard beaucoup de poesie

Pièces jointes:

Quelques photos rescentes qui m'ont ete offerte par un ami qui a voyage a Essaouira cet hiver.

Je sais on les a vu 1000 fois, mais bon c'est un nouveau regard beaucoup de poesie

Pièces jointes:

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:07 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:07 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:08 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:09 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:10 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:11 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:12 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:12 |

Administrateur Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 338 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 12 février 2009, 07:51 |

Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 1 622 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 20 avril 2009, 09:43 |

Membre depuis : 16 ans Messages: 2 159 |

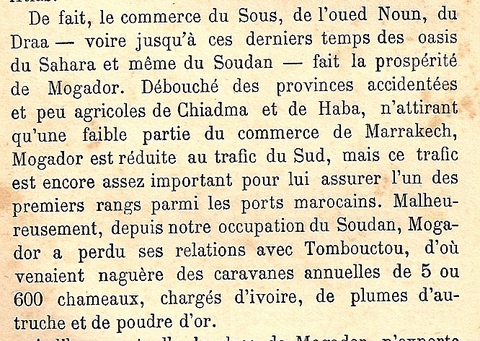

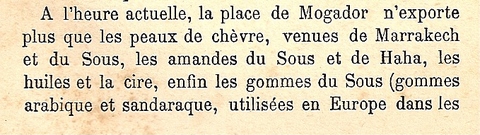

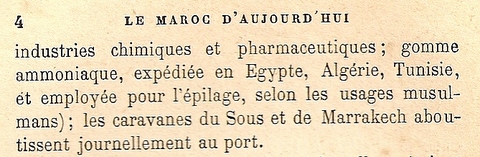

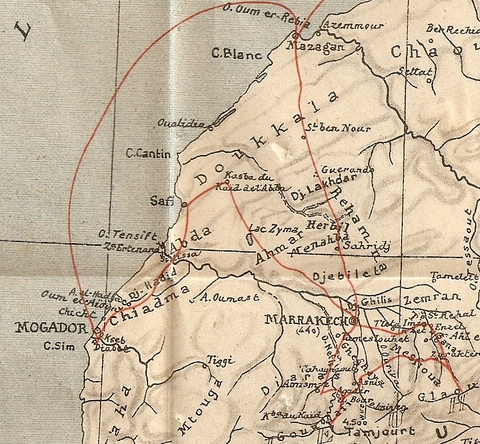

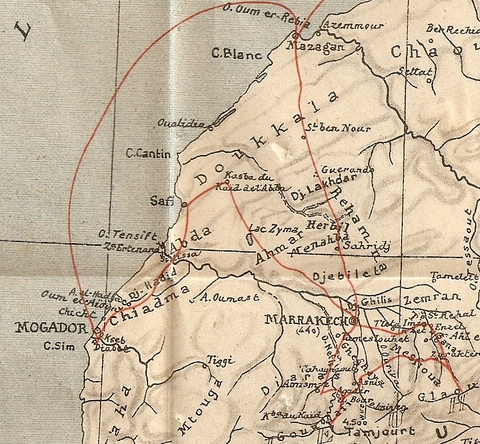

Le Voyage au Maroc de Eugène AUBIN (1902/1903)

Carte et textes extraits du livre "Le Maroc d'aujourd'hui" (librairie A.colin 1907)

Première partie du voyage : de Tanger à Mogador en bateau, à bord d'un vapeur anglais de la compagnie Forwood.

Mogador le 10 novembre 1902.

"...La construction de la nouvelle ville fut confiée au groupe assez nombreux de captifs chrétiens et de renégats retenus au Maroc. Un français, Cornut, originaire d'Avignon, en fut l'architecte..."

Lors de la fermeture du port d'Agadir, le commerce local se transporte à Mogador.

Pièces jointes:

Carte et textes extraits du livre "Le Maroc d'aujourd'hui" (librairie A.colin 1907)

Première partie du voyage : de Tanger à Mogador en bateau, à bord d'un vapeur anglais de la compagnie Forwood.

Mogador le 10 novembre 1902.

"...La construction de la nouvelle ville fut confiée au groupe assez nombreux de captifs chrétiens et de renégats retenus au Maroc. Un français, Cornut, originaire d'Avignon, en fut l'architecte..."

Lors de la fermeture du port d'Agadir, le commerce local se transporte à Mogador.

Pièces jointes:

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 20 avril 2009, 09:46 |

Membre depuis : 16 ans Messages: 2 159 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 20 avril 2009, 09:48 |

Membre depuis : 16 ans Messages: 2 159 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 20 avril 2009, 09:52 |

Membre depuis : 16 ans Messages: 2 159 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 20 avril 2009, 10:08 |

Membre depuis : 16 ans Messages: 2 159 |

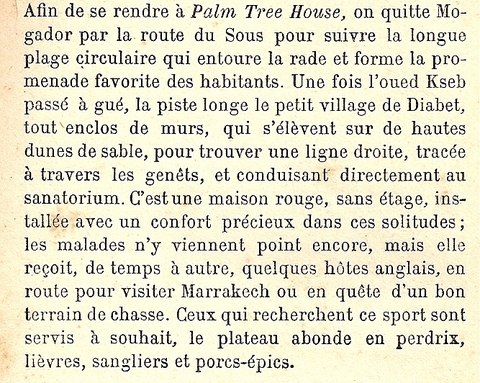

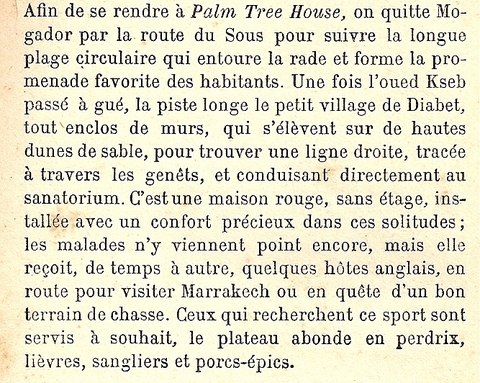

Eugène AUBIN à Mogador (1902)

"...Un jeune médecin d'Alger est venu cette année même s'installer à Mogador, où il a rejoint trois médecins : allemand, anglais et espagnol.

Le climat de Mogador est excellent, il oscille entre 15° et 25°. Les médecins affirment que ce serait une excellente station pour les gens malades de la poitrine, et qu'elle pourrait avantageusement, concourir avec Madère et les Canaries.

Un Gibraltarien, très en avance sur son temps, a établi un sanatorium à 10 km de la ville, sur un plateau rocheux recouvert de buissons de genêts, de lentisques et d'arganiers, qui s'étend entre la mer et les premiers contreforts de l'Atlas."

Notre ami Cigalou,archiviste accompli, aurait-il des documents concernant ce sanatorium ? Merci.

Nos amitiés

Pièces jointes:

"...Un jeune médecin d'Alger est venu cette année même s'installer à Mogador, où il a rejoint trois médecins : allemand, anglais et espagnol.

Le climat de Mogador est excellent, il oscille entre 15° et 25°. Les médecins affirment que ce serait une excellente station pour les gens malades de la poitrine, et qu'elle pourrait avantageusement, concourir avec Madère et les Canaries.

Un Gibraltarien, très en avance sur son temps, a établi un sanatorium à 10 km de la ville, sur un plateau rocheux recouvert de buissons de genêts, de lentisques et d'arganiers, qui s'étend entre la mer et les premiers contreforts de l'Atlas."

Notre ami Cigalou,archiviste accompli, aurait-il des documents concernant ce sanatorium ? Merci.

Nos amitiés

Pièces jointes:

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 30 juin 2009, 03:32 |

Membre depuis : 18 ans Messages: 3 208 |

The Last Jews of Essaouira (Jerusalem Post)

By BRETT KLINE

Josef Sebag says he has a fine life in his native Essaouira, though he has no friends here. This retail-artisan heaven for tourists on Morocco's southern Atlantic coast is a town unique in the Arab world for its history of Jewish-Muslim relations. He is often in his casbah antiques and book store, just off the large main square and next to the hippest night spot in town. Sebag does not hang out in the rooftop Taros Café, but does spend a good amount of time in London, Paris and New York. Something about living in Western cultural capitals suits him. He has friends there. Visitors come to see him, from France, Canada and Israel, but most tourists are not insiders in Essaouira, known as "Souira" to the locals. The Moroccan Arabs call him "el yahoudi" (the Jew) but Sebag says it is never meant nastily. He is as Moroccan and Souiri as they are, and they know it. His family has been in Morocco since fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. His store is a must for British, Australian, American and French tourists, as well as for surfers from all over and for increasing numbers of Israelis, especially the ones born in Morocco who don't come as part of organized tour groups. Most Moroccan and foreign Arabs do not come to his store, though it has nothing to do with Sebag's being a Jew. An exception is certain Arab authors who leave their poetry and prose with him, a sign of respect, as they know he carries few Arabic-language books. "I know everyone born and raised here but have few friends," he begins in French. "What can we talk about - art, literature? No, we can't. The local people are more concerned about making money in their stores and restaurants than reading. Some do very well here in Souira, but many have never been out of Morocco." Sebag is one of some 4,000 Jews still living in Morocco, mostly in Casablanca, but that is another story. He and his ailing mother are two of perhaps four - or seven or eight, depending on whom you ask - Jewish Essaouira natives left from a community that has lived here since 1760. ESSAOUIRA USED to be an example of a small Arab town in which Muslims and Jews lived side by side in both rich and poor districts, working together but socially segregated - and in peace. It was unique because there were almost as many Jews as there were Muslims, so the term "minority" did not really apply, as it did in every other town and city in Morocco and everywhere in the Arab world. Aside from ownership of the land in and around the town, which always remained in the hands of the caids and makhsen - local landed gentry and royal family clans - most urban-style import-export business was dominated by Jewish families. The one exception was all artisan work connected to wood, directly linked to the vast forests around the town. But as an example, from the very beginning of royal trading in the 18th century, the Corcos family dominated the import of tea leaves from Britain, which originated from its Far East colonies, and was thus responsible for making tea the traditional morning beverage in Morocco. Essaouira's last Jews began to leave following the Six Day War. Many of the working-class families left the mellah, the Jewish district in Arab cities, for Israel. The casbah's well-off business leaders headed mostly to France and Canada. But thousands of Jews remain here, buried in two cemeteries on the edge of town, including Rabbi Haim Pinto, whose tomb thousands of Jews from abroad visit every September in a hiloula, a pilgrimage. Today, real estate and tourism are booming in Essaouira, but the boom has little to do with the Jewish world, other than a few very active key players. The same is true for the music festivals, including the Gnawa Festival in June that draws up to 400,000 mostly Western visitors. "There are leading Moroccan Arab families here making a lot of money with French firms in construction and tourism-linked activities in general, and that is grand for them and for the town," Sebag says, "but let's say that aside from the music festivals, culture is limited. Jews here were always a bridge between small-town Muslim society and the Western world. There were very few tourists here. Now the opposite is true. The Jews are gone, but Souira is a tourist center." The walled city is home to hundreds of boutiques, some of which are attached to small workshops, often with two stories of apartments above. Restaurants and cafés are everywhere. Visitors check out the ramparts, the port and historical sites, walking for kilometers along the beaches in the wind that blows 20 hours a day. They drive to the surrounding villages, or surf, also a big attraction here. When people are anywhere inside the walls, the impulse to buy and buy again in the casbah and medina is overwhelming. Visitors walk up and down the car-free streets and allies, purchasing fantastically colored rugs and scarves. They buy blue Gnawa cotton robes and head pieces, more clothing, bed linen in gorgeous muted colors, paintings, silver jewelry, leather footwear, metal lamps and objects and intricate wooden boxes and ornate tables. Essaouira was known as Mogador until the end of French colonial rule in the early 1960s. Portuguese occupiers built the wall and ramparts, known as Castello Real, in 1505 before Mogador was much of a town, but the inhabitants of the Arab Chiadma region to the north and the Berber Haha to the south gave them no peace, and by 1512 the Portuguese were pulling out and sacking much of the region. Mogador, cité sous les alizées or "Mogador, a town in the wind" was written by Hamza Ben Driss Ottmani, a French grande-école graduate and public-sector research director in Rabat born of a well-known family in Essaouira. Ottmani offers accounts of all the local villages, written in 1516 by celebrated traveler and author known as Leon the African. Born El Hassan Ben Muhammad el-Ouazzan el-Gharnati in Grenada, Spain in 1483, he moved with his family to Fez in Morocco when Grenada was taken by the Catholic kings in 1492. IN THE southern Berber Haha region, in prosperous and long-gone villages with names like Tednest, Hadecchis and Eitdeuet, Berber Jews were a majority or close to it, in a totally Muslim world. Very little is known about these tens of thousands of people who lived in relative comfort in this tiny isolated corner of Jewish and Moroccan history. The Berber Jews are thought to have been there since the destruction of the Temple. And it is believed that hundreds of thousands of other people in southern Morocco are Islamic converts of Jewish origin. Long before Leon the African, this area produced the royal purple color of the Roman Empire from mollusks on the coast that was busy with trading ships. Even earlier, the Phoenicians bought argan oil here; 2,500 years later, argan oil is still made here and only here. Argan, used sometimes as salad oil but mostly as a skin product rich in vitamin E, is a growing organic rage in France and Europe - very expensive and not without a certain intrigue. Essaouira's real beginning as a import-export center came in 1760 when the sultan of Morocco appointed families from Casablanca, Marrakech and other northern cities to settle here and become official royal traders. Many if not most were Jewish. The town grew. According to Ottmani, seven of the town's leading families in the 19th century were Muslim, while 25 were Jewish, with names such as Corcos, Afriat, Bensaoud, Cohen Solal, Belisha, Ohana, Pinto and El-Maleh. In the beginning, these families conducted trade by ship mostly with Britain, but also handled local trade and the camel caravans coming from Timbuktu across the desert, with links to Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Cairo and Mecca. In modern times the caravans disappeared, but international trade focused on Europe became highly competitive. The railroad built by the French in 1912 on did not reach Essaouira from Marrakech, today a two-hour bus ride away. Casablanca and Tangiers were deemed much more important, and the glory and prosperity of the town in the wind slowly began to fade. Its leading citizens were still Muslim, Jewish and European, but there also were thousands of working-class Muslims and Jews. Essaouira was known for its artisan work, using wood from the close-by thuya and argania trees to make ornate, silver and stone-inlaid tables and mirrors. This was an exclusively Muslim sector. The silver jewelry work was famous for the much sought-after filogram design, the Dag Ed Essaouiri - thin lines converge on a circular center as meticulous radii, a design that was instantly recognizable as native to Essaouira. The master silversmiths were all Jewish, as were many of the workers, who lived mostly in the mellah. Today, the remaining silver designers are Berbers, many of whom worked with the local Jews until they left. The local Arab jewelers all work in gold. SUDDENLY, AN Israeli couple enters Sebag's bookstore, and there are smiles and greetings in French, Maghrebi Arabic and Hebrew. Isaac Azencot was born and raised in the mellah and at 16 left with his parents for Israel. His father was a cantor in one of the 30 local synagogues, none of which exists today. "My parents were Zionists," he says, "so we left. But they remained Moroccans their entire lives, and I've done the same. I'm proud to be a Moroccan-Israeli." His Hebrew is obviously fluent, with a Moroccan accent; his French is good, if rusty; his English very good, and his Maghrebi Arabic is native and still fluent, with a good Arab accent. "Sbahelchir, la besse halik," he says, meaning, "good morning, everything is fine." His brother, a professor, directs all research on Essaouira at the University of Haifa, near their hometown of Kiryat Ata, complete with original documents transferred from Morocco. "It feels good to see old Muslim friends here in Souira," Azencot says sincerely, in English. "We all lived modestly and respectfully back then, and we boys in the mellah had Muslim friends." But, he adds, they lived differently. He mentions the Alliance Française school right away. "We were 28 Jewish boys and girls in the class, but there was only one Muslim boy," he says. "It wasn't the money. Working-class Muslims simply didn't learn to read and write back then. And then we all left, except for Josef and his mother." He laughs. "Ambitious Muslim young people left also," Sebag breaks in. "And I can only live here by leaving regularly. There is no future for Jews here, or anywhere in Morocco. Today, with all the tourism development, no bridge is needed to the Western world." THERE IS only one native Israeli living full-time in Essaouira. Noam Nir-Boujo has done well for the past nine years serving lunches and dinners at his restaurant, the Riad al Baraka, outside the casbah on the pedestrian Rue Med Al Qorry. The long, narrow, hectic commercial street leads to the most authentic luxury hotel in town, L'Heure Bleue, before ending at the Bab Marrakech gate of the original walled town. Filled with local schoolkids and shoppers, resident foreigners, tourists and all kinds of characters, the street is lined with shops and tiny leather and metal workshops. The Riad al Baraka occupies a lovely building and garden courtyard. Totally hidden from the busy street behind a large wooden door, it was a private Jewish girls' school until the 1940s. Nir-Boujo was born in Tel Aviv. His father and grandfather were born in Essaouira. His up-front talking to people and sometimes making strong statements about tourism and coexistence in Essaouira, and simply having a big picture of the world, make him a stand-alone type of guy in this town. In fact, he is a new kind of bridge, definitely a Westerner, but a "Souiri" by origin who speaks fluent Maghrebi Arabic. "People make money here," Nir-Boujo says, "but they remain suspicious about outsiders. Everyone here knows I'm Jewish, but only some know I'm Israeli. There is ignorance, but never trouble." He notes that almost all women wear hijabs in public but says this is due more to conservative social codes than religious pressure. Several thousand Westerners have bought homes and businesses in Essaouira over the past two decades. Nir-Boujo says that today the expat community includes perhaps 60 to 80 Jews from France, Britain and Canada. Few foreigners live here full time. Modern Essaouira has been mostly off the map, although in the late '60s and early '70s, it was a stop on the international hippy circuit. Jimi Hendrix hung out here, and had a house in a nearby village. Israel has been a part of the attempt to commercialize. There is an ongoing attempt to link French-speaking Jews back to their countries of origin in North Africa. In some cases, it has been successful, as French and Canadian Sephardim, and in some cases Israelis, have bought homes there. "Remember, a Parisian or a Tel Avivian of Moroccan-born parents never loses his Moroccan nationality," Nir-Boujo notes with a wry smile. "But think about it, where in the Arab world would Jews from any country buy a home and feel fully safe? Perhaps in Tunisia, but nowhere else." THE RIAD al Baraka is full of soft colors, ochre and blues and greens under soft lighting, with round corners and doorways, all surrounding a garden. Nir-Boujo's food is a modern take on classics. The couscous, for example, is compact and orderly, and packed with fresh flavor. The chicken and lamb are soft. Jewish-Arab-Andalusian music wafts in over courtyard speakers. The restaurateur has a photo of the young Moroccan king, Mohamed VI, above the reception desk. He is proud to be an Israeli with origins in Souira, and is happy living here. He speaks Hebrew, Maghrebi-Arabic, English and French, in that order. "It is clear that Morocco is the most Jewish-friendly country in the entire Arab world, but the ignorance is still here," he says. "Remember, the parents of young adults here lived and worked side by side with Moroccan Jews, and almost all will tell you they would love to see the Jews return. But the young people know nothing about Jews. They know only the clichés they see on Arab cable television, mostly nasty Israeli soldiers hitting Palestinians. They've also heard that Jews are all rich." Nir-Boujo's observation was easily confirmed by Fatimzara Ottmani, niece of the author of the Mogador history, and manager of the family-owned Ramses restaurant in the casbah. Twenty-something and without a hijab in public, she smiles easily and kisses foreign male acquaintances on both cheeks, French-style. Of course, she serves fish. The local port is very busy, and has been for hundreds of years. Essaouira still supplies hundreds of restaurants in Marrakech with fresh catch. But there is also a Moroccan Jewish Shabbat d'fina on the menu, made with bulgur wheat, chickpeas, chunks of beef and hard boiled eggs, in honor of her Jewish great-aunt, from a very rare mixed marriage years ago. And it sells well in the small dining area that looks and feels like a cozy Moroccan living room. Unlike her father and uncle, Ottmani is not well-educated and her French is not great. She is outgoing and funny, but knows little local history and has not read her uncle's books. In fact, she rarely reads at all, preferring to watch TV with her boyfriend. She has never been outside Morocco and doesn't really care to go. But she does have insight. "My father and uncle Hamza grew up here in the casbah with Jewish kids," she begins. "The men in moneyed Muslim families received a good French-language high-school education here, just like the Jews. It was the language of the educated and the government." For her generation, French tourists and residents have replaced the Jews as an international influence. "But I would love to see young Jews, especially Moroccans, living here," she says. "It would bring more wealth and prosperity. Of course it would. And that would be great for all of us." "Essaouira is a small town with a fabulous heritage in a developing country," says Nir-Boujo. "There is work to be done here, and I know that certain people in Rabat and Casablanca know that." He won't say more. It is not his role to do that, and he knows it. His role is the Essaouira representative of the World Federation of Moroccan Jewry, and he also sits on a local tourism board. He was just back from a three-day hiloula, the annual traditional Jewish religious pilgrimages held at different times all over Morocco and Tunisia. This year there was one in Safi, an hour or so up the coast, a center of ceramic arts. He says that three Jewish families still live there, but the 300 participants were mostly elderly men from France, Canada and Israel. "It was fascinating and moving," he says. Nir-Boujo knows little about traditional Sephardi religious practices. He noted that the ouli of Safi, the king's official representative, has said that there is an unbreakable connection between Morocco and Jews. "His hospitality was wonderful," he says. The hiloula was the subject of reports on Moroccan national television in both French and Arabic, presented as a piece of the country's religious and cultural heritage. "That is a very positive statement about Jews here," he adds. SUDDENLY HE is busy discussing dinner plans for 15 with someone in Hebrew with a good amount of Maghrebi-Arabic thrown in. Dr. Yehuda Ben-Simon is dean of students at Western Galilee College near Acre. White haired and pony-tailed, he is also a tour guide, bringing Israelis to his native Morocco. His father was a noted Hebrew-language printer in Casablanca, and he also speaks and reads fluent Arabic, French and English. Ben-Simon says Israelis come to Essaouira all year round, mostly in tour groups such as his. "Some are of Moroccan origin, others not," he says. "Generally, they find the country fascinating. But other Israelis who have never been... associate Morocco with a place like Egypt, because it is Arab, and they are afraid. Israelis can be ignorant, too." A trying moment came in December, during the incursion into Gaza. Nir-Boujo was a bit nervous, though not for any particular reason, and had gone to see local police officials. A local demonstration one day in support of Gazans had attracted about 500 people, and had remained quiet and peaceful. The police, who know exactly who Nir-Boujo is and where he comes from, and appreciate his activity with local tourism officials, told him, "Keep your eyes open, but you have nothing to fear. We're watching out for you." Local police officials told him that there was no radical Islamic activity in town. "If any Arab foreigners come looking for trouble, Algerians for example, we know about it," they said. "Nobody has come." All radical Islamic activity in Morocco over the past several years has been linked to Algerians and the branch of al-Qaida trying to establish itself in Casablanca. Currently the restaurant business is slow in Souira. Nir-Boujo has formed a travel company. One of his first clients is a big Israeli travel firm. "I want to mix business with social," he says, "so 2.5 percent of profits will go to Jewish restoration projects in Morocco, and 2.5% will go to not-for-profit education projects throughout the country. "This is my personal mission here. In Israel and Western countries, this business-social mix happens regularly, but here it does not. It comes from the tzedaka tradition and the chora for Muslims, but perhaps needs some encouraging here." He will be going to Casablanca to talk to Jewish businessmen there about doing the same mix, but would like to work with Moroccan Muslim businesspeople as well. IS IT strange that no other Israelis have followed Nir-Boujo to live in Essaouira? "No, I'm not a typical Israeli, I am Moroccan," he says. "The mix of the heartfelt and the official identity is tough to describe. I would say I am still Israeli, but I am also a Moroccan patriot. It would take a strange person to move here full-time." He says that at any time there are tourist groups from Israel in Morocco, and some make it to Essaouira. But business is still slow, for everyone. All the local cultural and tourism business development, from the music festivals to ongoing construction sites, are linked to the efforts of one man, one of the few important Jews remaining in the Arab world. Distinguished and perhaps above all discreet, André Azoulay is the chief financial adviser to King Mohamed VI and his father King Hassan II before him. He is a well-traveled international banker and is active on the global diplomatic scene. He has also been a tireless worker over the years for peace between Israelis and Palestinians, known for saying, "The security of Israel is based on the establishing of a Palestinian state," as far back as 1990. Azoulay is currently based in the Moroccan capital Rabat, but was born and raised in Essaouira, on a small square in the casbah. Across the square, his wife was also born and raised, next to the synagogue, today a café. The square is full of carpets and clothing, and antique wooden and metal objects, including menorot, all for sale. The "godfather of Essaouira" and a very proud Jew, Azoulay has helped put together and backed all the live music festivals here, especially the Gnawa Festival, playing the role to the fullest, going on stage to open the festivities. He has brought French and American hotel investment, jobs and prosperity. He walks the casbah streets, greeting friends and former neighbors with hugs and kisses, asking about the health of their families. He helped put together a recent 10-day Moroccan Jewish conference and concert series in Paris, which many Israelis attended. One of the most relaxed speakers was Morocco's then ambassador to France, Abdel-Fettah Sijilmassi. A 1970 Israeli documentary on Essaouira was screened during the conference. In it, moshav-born teenagers in Galilee discover that their grandfather, Rabbi David El Kaim, was a renowned scholar and liturgical poet in Essaouira. Those boys are now in their 50s. If they have kids of their own, what do their children know about the great-grandfather, rabbi and poet from Essaouira? He was yet another element in the unique Arab-Jewish history of a Moroccan coast town where the present looks to the past and the future. Cultural-historical research and artisan commerce could nourish the Jewish-Arab magic and prosperity of Essaouira, with the ever-present wind blowing it into a bright future.

By BRETT KLINE

Josef Sebag says he has a fine life in his native Essaouira, though he has no friends here. This retail-artisan heaven for tourists on Morocco's southern Atlantic coast is a town unique in the Arab world for its history of Jewish-Muslim relations. He is often in his casbah antiques and book store, just off the large main square and next to the hippest night spot in town. Sebag does not hang out in the rooftop Taros Café, but does spend a good amount of time in London, Paris and New York. Something about living in Western cultural capitals suits him. He has friends there. Visitors come to see him, from France, Canada and Israel, but most tourists are not insiders in Essaouira, known as "Souira" to the locals. The Moroccan Arabs call him "el yahoudi" (the Jew) but Sebag says it is never meant nastily. He is as Moroccan and Souiri as they are, and they know it. His family has been in Morocco since fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. His store is a must for British, Australian, American and French tourists, as well as for surfers from all over and for increasing numbers of Israelis, especially the ones born in Morocco who don't come as part of organized tour groups. Most Moroccan and foreign Arabs do not come to his store, though it has nothing to do with Sebag's being a Jew. An exception is certain Arab authors who leave their poetry and prose with him, a sign of respect, as they know he carries few Arabic-language books. "I know everyone born and raised here but have few friends," he begins in French. "What can we talk about - art, literature? No, we can't. The local people are more concerned about making money in their stores and restaurants than reading. Some do very well here in Souira, but many have never been out of Morocco." Sebag is one of some 4,000 Jews still living in Morocco, mostly in Casablanca, but that is another story. He and his ailing mother are two of perhaps four - or seven or eight, depending on whom you ask - Jewish Essaouira natives left from a community that has lived here since 1760. ESSAOUIRA USED to be an example of a small Arab town in which Muslims and Jews lived side by side in both rich and poor districts, working together but socially segregated - and in peace. It was unique because there were almost as many Jews as there were Muslims, so the term "minority" did not really apply, as it did in every other town and city in Morocco and everywhere in the Arab world. Aside from ownership of the land in and around the town, which always remained in the hands of the caids and makhsen - local landed gentry and royal family clans - most urban-style import-export business was dominated by Jewish families. The one exception was all artisan work connected to wood, directly linked to the vast forests around the town. But as an example, from the very beginning of royal trading in the 18th century, the Corcos family dominated the import of tea leaves from Britain, which originated from its Far East colonies, and was thus responsible for making tea the traditional morning beverage in Morocco. Essaouira's last Jews began to leave following the Six Day War. Many of the working-class families left the mellah, the Jewish district in Arab cities, for Israel. The casbah's well-off business leaders headed mostly to France and Canada. But thousands of Jews remain here, buried in two cemeteries on the edge of town, including Rabbi Haim Pinto, whose tomb thousands of Jews from abroad visit every September in a hiloula, a pilgrimage. Today, real estate and tourism are booming in Essaouira, but the boom has little to do with the Jewish world, other than a few very active key players. The same is true for the music festivals, including the Gnawa Festival in June that draws up to 400,000 mostly Western visitors. "There are leading Moroccan Arab families here making a lot of money with French firms in construction and tourism-linked activities in general, and that is grand for them and for the town," Sebag says, "but let's say that aside from the music festivals, culture is limited. Jews here were always a bridge between small-town Muslim society and the Western world. There were very few tourists here. Now the opposite is true. The Jews are gone, but Souira is a tourist center." The walled city is home to hundreds of boutiques, some of which are attached to small workshops, often with two stories of apartments above. Restaurants and cafés are everywhere. Visitors check out the ramparts, the port and historical sites, walking for kilometers along the beaches in the wind that blows 20 hours a day. They drive to the surrounding villages, or surf, also a big attraction here. When people are anywhere inside the walls, the impulse to buy and buy again in the casbah and medina is overwhelming. Visitors walk up and down the car-free streets and allies, purchasing fantastically colored rugs and scarves. They buy blue Gnawa cotton robes and head pieces, more clothing, bed linen in gorgeous muted colors, paintings, silver jewelry, leather footwear, metal lamps and objects and intricate wooden boxes and ornate tables. Essaouira was known as Mogador until the end of French colonial rule in the early 1960s. Portuguese occupiers built the wall and ramparts, known as Castello Real, in 1505 before Mogador was much of a town, but the inhabitants of the Arab Chiadma region to the north and the Berber Haha to the south gave them no peace, and by 1512 the Portuguese were pulling out and sacking much of the region. Mogador, cité sous les alizées or "Mogador, a town in the wind" was written by Hamza Ben Driss Ottmani, a French grande-école graduate and public-sector research director in Rabat born of a well-known family in Essaouira. Ottmani offers accounts of all the local villages, written in 1516 by celebrated traveler and author known as Leon the African. Born El Hassan Ben Muhammad el-Ouazzan el-Gharnati in Grenada, Spain in 1483, he moved with his family to Fez in Morocco when Grenada was taken by the Catholic kings in 1492. IN THE southern Berber Haha region, in prosperous and long-gone villages with names like Tednest, Hadecchis and Eitdeuet, Berber Jews were a majority or close to it, in a totally Muslim world. Very little is known about these tens of thousands of people who lived in relative comfort in this tiny isolated corner of Jewish and Moroccan history. The Berber Jews are thought to have been there since the destruction of the Temple. And it is believed that hundreds of thousands of other people in southern Morocco are Islamic converts of Jewish origin. Long before Leon the African, this area produced the royal purple color of the Roman Empire from mollusks on the coast that was busy with trading ships. Even earlier, the Phoenicians bought argan oil here; 2,500 years later, argan oil is still made here and only here. Argan, used sometimes as salad oil but mostly as a skin product rich in vitamin E, is a growing organic rage in France and Europe - very expensive and not without a certain intrigue. Essaouira's real beginning as a import-export center came in 1760 when the sultan of Morocco appointed families from Casablanca, Marrakech and other northern cities to settle here and become official royal traders. Many if not most were Jewish. The town grew. According to Ottmani, seven of the town's leading families in the 19th century were Muslim, while 25 were Jewish, with names such as Corcos, Afriat, Bensaoud, Cohen Solal, Belisha, Ohana, Pinto and El-Maleh. In the beginning, these families conducted trade by ship mostly with Britain, but also handled local trade and the camel caravans coming from Timbuktu across the desert, with links to Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Cairo and Mecca. In modern times the caravans disappeared, but international trade focused on Europe became highly competitive. The railroad built by the French in 1912 on did not reach Essaouira from Marrakech, today a two-hour bus ride away. Casablanca and Tangiers were deemed much more important, and the glory and prosperity of the town in the wind slowly began to fade. Its leading citizens were still Muslim, Jewish and European, but there also were thousands of working-class Muslims and Jews. Essaouira was known for its artisan work, using wood from the close-by thuya and argania trees to make ornate, silver and stone-inlaid tables and mirrors. This was an exclusively Muslim sector. The silver jewelry work was famous for the much sought-after filogram design, the Dag Ed Essaouiri - thin lines converge on a circular center as meticulous radii, a design that was instantly recognizable as native to Essaouira. The master silversmiths were all Jewish, as were many of the workers, who lived mostly in the mellah. Today, the remaining silver designers are Berbers, many of whom worked with the local Jews until they left. The local Arab jewelers all work in gold. SUDDENLY, AN Israeli couple enters Sebag's bookstore, and there are smiles and greetings in French, Maghrebi Arabic and Hebrew. Isaac Azencot was born and raised in the mellah and at 16 left with his parents for Israel. His father was a cantor in one of the 30 local synagogues, none of which exists today. "My parents were Zionists," he says, "so we left. But they remained Moroccans their entire lives, and I've done the same. I'm proud to be a Moroccan-Israeli." His Hebrew is obviously fluent, with a Moroccan accent; his French is good, if rusty; his English very good, and his Maghrebi Arabic is native and still fluent, with a good Arab accent. "Sbahelchir, la besse halik," he says, meaning, "good morning, everything is fine." His brother, a professor, directs all research on Essaouira at the University of Haifa, near their hometown of Kiryat Ata, complete with original documents transferred from Morocco. "It feels good to see old Muslim friends here in Souira," Azencot says sincerely, in English. "We all lived modestly and respectfully back then, and we boys in the mellah had Muslim friends." But, he adds, they lived differently. He mentions the Alliance Française school right away. "We were 28 Jewish boys and girls in the class, but there was only one Muslim boy," he says. "It wasn't the money. Working-class Muslims simply didn't learn to read and write back then. And then we all left, except for Josef and his mother." He laughs. "Ambitious Muslim young people left also," Sebag breaks in. "And I can only live here by leaving regularly. There is no future for Jews here, or anywhere in Morocco. Today, with all the tourism development, no bridge is needed to the Western world." THERE IS only one native Israeli living full-time in Essaouira. Noam Nir-Boujo has done well for the past nine years serving lunches and dinners at his restaurant, the Riad al Baraka, outside the casbah on the pedestrian Rue Med Al Qorry. The long, narrow, hectic commercial street leads to the most authentic luxury hotel in town, L'Heure Bleue, before ending at the Bab Marrakech gate of the original walled town. Filled with local schoolkids and shoppers, resident foreigners, tourists and all kinds of characters, the street is lined with shops and tiny leather and metal workshops. The Riad al Baraka occupies a lovely building and garden courtyard. Totally hidden from the busy street behind a large wooden door, it was a private Jewish girls' school until the 1940s. Nir-Boujo was born in Tel Aviv. His father and grandfather were born in Essaouira. His up-front talking to people and sometimes making strong statements about tourism and coexistence in Essaouira, and simply having a big picture of the world, make him a stand-alone type of guy in this town. In fact, he is a new kind of bridge, definitely a Westerner, but a "Souiri" by origin who speaks fluent Maghrebi Arabic. "People make money here," Nir-Boujo says, "but they remain suspicious about outsiders. Everyone here knows I'm Jewish, but only some know I'm Israeli. There is ignorance, but never trouble." He notes that almost all women wear hijabs in public but says this is due more to conservative social codes than religious pressure. Several thousand Westerners have bought homes and businesses in Essaouira over the past two decades. Nir-Boujo says that today the expat community includes perhaps 60 to 80 Jews from France, Britain and Canada. Few foreigners live here full time. Modern Essaouira has been mostly off the map, although in the late '60s and early '70s, it was a stop on the international hippy circuit. Jimi Hendrix hung out here, and had a house in a nearby village. Israel has been a part of the attempt to commercialize. There is an ongoing attempt to link French-speaking Jews back to their countries of origin in North Africa. In some cases, it has been successful, as French and Canadian Sephardim, and in some cases Israelis, have bought homes there. "Remember, a Parisian or a Tel Avivian of Moroccan-born parents never loses his Moroccan nationality," Nir-Boujo notes with a wry smile. "But think about it, where in the Arab world would Jews from any country buy a home and feel fully safe? Perhaps in Tunisia, but nowhere else." THE RIAD al Baraka is full of soft colors, ochre and blues and greens under soft lighting, with round corners and doorways, all surrounding a garden. Nir-Boujo's food is a modern take on classics. The couscous, for example, is compact and orderly, and packed with fresh flavor. The chicken and lamb are soft. Jewish-Arab-Andalusian music wafts in over courtyard speakers. The restaurateur has a photo of the young Moroccan king, Mohamed VI, above the reception desk. He is proud to be an Israeli with origins in Souira, and is happy living here. He speaks Hebrew, Maghrebi-Arabic, English and French, in that order. "It is clear that Morocco is the most Jewish-friendly country in the entire Arab world, but the ignorance is still here," he says. "Remember, the parents of young adults here lived and worked side by side with Moroccan Jews, and almost all will tell you they would love to see the Jews return. But the young people know nothing about Jews. They know only the clichés they see on Arab cable television, mostly nasty Israeli soldiers hitting Palestinians. They've also heard that Jews are all rich." Nir-Boujo's observation was easily confirmed by Fatimzara Ottmani, niece of the author of the Mogador history, and manager of the family-owned Ramses restaurant in the casbah. Twenty-something and without a hijab in public, she smiles easily and kisses foreign male acquaintances on both cheeks, French-style. Of course, she serves fish. The local port is very busy, and has been for hundreds of years. Essaouira still supplies hundreds of restaurants in Marrakech with fresh catch. But there is also a Moroccan Jewish Shabbat d'fina on the menu, made with bulgur wheat, chickpeas, chunks of beef and hard boiled eggs, in honor of her Jewish great-aunt, from a very rare mixed marriage years ago. And it sells well in the small dining area that looks and feels like a cozy Moroccan living room. Unlike her father and uncle, Ottmani is not well-educated and her French is not great. She is outgoing and funny, but knows little local history and has not read her uncle's books. In fact, she rarely reads at all, preferring to watch TV with her boyfriend. She has never been outside Morocco and doesn't really care to go. But she does have insight. "My father and uncle Hamza grew up here in the casbah with Jewish kids," she begins. "The men in moneyed Muslim families received a good French-language high-school education here, just like the Jews. It was the language of the educated and the government." For her generation, French tourists and residents have replaced the Jews as an international influence. "But I would love to see young Jews, especially Moroccans, living here," she says. "It would bring more wealth and prosperity. Of course it would. And that would be great for all of us." "Essaouira is a small town with a fabulous heritage in a developing country," says Nir-Boujo. "There is work to be done here, and I know that certain people in Rabat and Casablanca know that." He won't say more. It is not his role to do that, and he knows it. His role is the Essaouira representative of the World Federation of Moroccan Jewry, and he also sits on a local tourism board. He was just back from a three-day hiloula, the annual traditional Jewish religious pilgrimages held at different times all over Morocco and Tunisia. This year there was one in Safi, an hour or so up the coast, a center of ceramic arts. He says that three Jewish families still live there, but the 300 participants were mostly elderly men from France, Canada and Israel. "It was fascinating and moving," he says. Nir-Boujo knows little about traditional Sephardi religious practices. He noted that the ouli of Safi, the king's official representative, has said that there is an unbreakable connection between Morocco and Jews. "His hospitality was wonderful," he says. The hiloula was the subject of reports on Moroccan national television in both French and Arabic, presented as a piece of the country's religious and cultural heritage. "That is a very positive statement about Jews here," he adds. SUDDENLY HE is busy discussing dinner plans for 15 with someone in Hebrew with a good amount of Maghrebi-Arabic thrown in. Dr. Yehuda Ben-Simon is dean of students at Western Galilee College near Acre. White haired and pony-tailed, he is also a tour guide, bringing Israelis to his native Morocco. His father was a noted Hebrew-language printer in Casablanca, and he also speaks and reads fluent Arabic, French and English. Ben-Simon says Israelis come to Essaouira all year round, mostly in tour groups such as his. "Some are of Moroccan origin, others not," he says. "Generally, they find the country fascinating. But other Israelis who have never been... associate Morocco with a place like Egypt, because it is Arab, and they are afraid. Israelis can be ignorant, too." A trying moment came in December, during the incursion into Gaza. Nir-Boujo was a bit nervous, though not for any particular reason, and had gone to see local police officials. A local demonstration one day in support of Gazans had attracted about 500 people, and had remained quiet and peaceful. The police, who know exactly who Nir-Boujo is and where he comes from, and appreciate his activity with local tourism officials, told him, "Keep your eyes open, but you have nothing to fear. We're watching out for you." Local police officials told him that there was no radical Islamic activity in town. "If any Arab foreigners come looking for trouble, Algerians for example, we know about it," they said. "Nobody has come." All radical Islamic activity in Morocco over the past several years has been linked to Algerians and the branch of al-Qaida trying to establish itself in Casablanca. Currently the restaurant business is slow in Souira. Nir-Boujo has formed a travel company. One of his first clients is a big Israeli travel firm. "I want to mix business with social," he says, "so 2.5 percent of profits will go to Jewish restoration projects in Morocco, and 2.5% will go to not-for-profit education projects throughout the country. "This is my personal mission here. In Israel and Western countries, this business-social mix happens regularly, but here it does not. It comes from the tzedaka tradition and the chora for Muslims, but perhaps needs some encouraging here." He will be going to Casablanca to talk to Jewish businessmen there about doing the same mix, but would like to work with Moroccan Muslim businesspeople as well. IS IT strange that no other Israelis have followed Nir-Boujo to live in Essaouira? "No, I'm not a typical Israeli, I am Moroccan," he says. "The mix of the heartfelt and the official identity is tough to describe. I would say I am still Israeli, but I am also a Moroccan patriot. It would take a strange person to move here full-time." He says that at any time there are tourist groups from Israel in Morocco, and some make it to Essaouira. But business is still slow, for everyone. All the local cultural and tourism business development, from the music festivals to ongoing construction sites, are linked to the efforts of one man, one of the few important Jews remaining in the Arab world. Distinguished and perhaps above all discreet, André Azoulay is the chief financial adviser to King Mohamed VI and his father King Hassan II before him. He is a well-traveled international banker and is active on the global diplomatic scene. He has also been a tireless worker over the years for peace between Israelis and Palestinians, known for saying, "The security of Israel is based on the establishing of a Palestinian state," as far back as 1990. Azoulay is currently based in the Moroccan capital Rabat, but was born and raised in Essaouira, on a small square in the casbah. Across the square, his wife was also born and raised, next to the synagogue, today a café. The square is full of carpets and clothing, and antique wooden and metal objects, including menorot, all for sale. The "godfather of Essaouira" and a very proud Jew, Azoulay has helped put together and backed all the live music festivals here, especially the Gnawa Festival, playing the role to the fullest, going on stage to open the festivities. He has brought French and American hotel investment, jobs and prosperity. He walks the casbah streets, greeting friends and former neighbors with hugs and kisses, asking about the health of their families. He helped put together a recent 10-day Moroccan Jewish conference and concert series in Paris, which many Israelis attended. One of the most relaxed speakers was Morocco's then ambassador to France, Abdel-Fettah Sijilmassi. A 1970 Israeli documentary on Essaouira was screened during the conference. In it, moshav-born teenagers in Galilee discover that their grandfather, Rabbi David El Kaim, was a renowned scholar and liturgical poet in Essaouira. Those boys are now in their 50s. If they have kids of their own, what do their children know about the great-grandfather, rabbi and poet from Essaouira? He was yet another element in the unique Arab-Jewish history of a Moroccan coast town where the present looks to the past and the future. Cultural-historical research and artisan commerce could nourish the Jewish-Arab magic and prosperity of Essaouira, with the ever-present wind blowing it into a bright future.

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 29 juillet 2009, 10:01 |

Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 1 622 |

|

Re: Mogador, Essaouira, suite 02 août 2009, 03:42 |

Membre depuis : 19 ans Messages: 1 622 |

Seuls les utilisateurs enregistrés peuvent poster des messages dans ce forum.